Last year, I had a chance to contribute to a collection of prayers written by a diverse group of Christian women. Curated by Sarah Bessey, A Rhythm of Prayer debuted earlier this year and made bestseller lists in Canada and the United States.

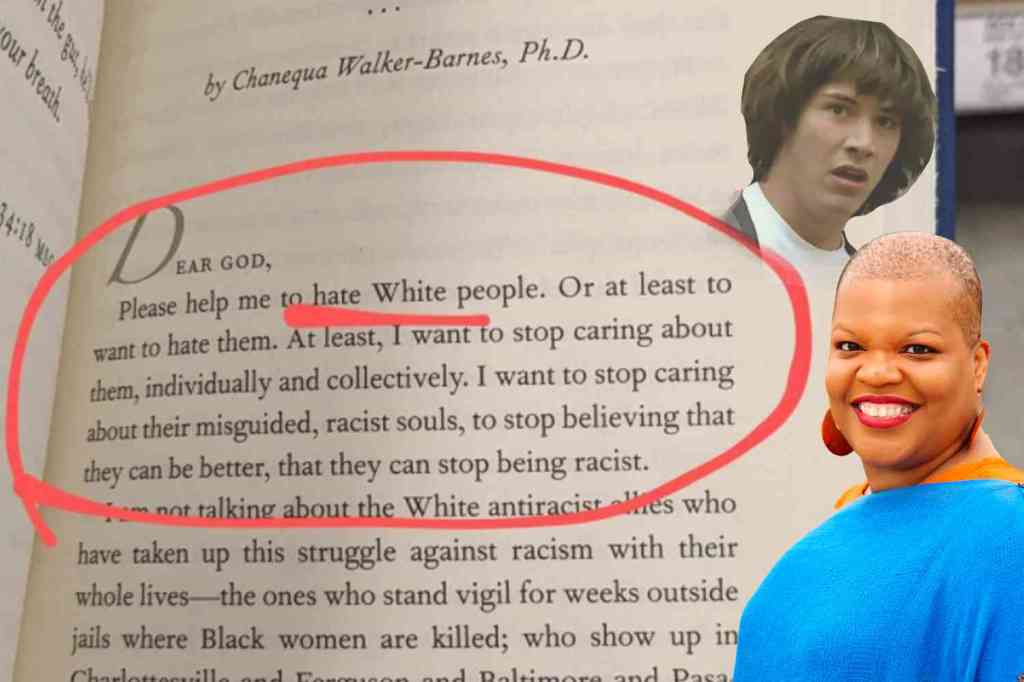

It is a strongly worded prayer. Modeled after the imprecatory psalms, it begins, “Dear God, please help me to hate White people.” Since it’s already circulating online, I’m including the full text below. I urge you to purchase the book as well.

Let me share a bit of background about the prayer. I wrote it in a heated moment. A White person – someone whom I would have called a friend – dropped the N-word in a casual conversation. Notice that I didn’t write it out. That’s because I don’t. I don’t say it either, especially not with a hard -er. The word is traumatic for me. I am a lifelong southerner who is only one generation removed from sharecropping. My family history is full of racial trauma. When my paternal grandfather was 7, he and his father ran away from the White South Carolina farmer for whom they sharecropped. This would have been around 1915, fifty years after the end of slavery, and they had to escape under the cover of darkness because sharecropping was just another form of slavery. Later, his family would be the second Black family to move onto his street; his children would integrate their high schools, putting their educations in the hands of racist White teachers who did not honor their potential. And that’s just one side of my family; my maternal side has similar stories, including the murder of a family member who was a civil rights activist. The N-word is not a word we use because it is a word that comes with memory, painful and traumatic memory.

So I was hella triggered when that person used the N-word. And I was already past deadline for my contribution. I could have done a lot with that rage. I could have sought vengeance, maybe putting the person on social media blast in order to try to ruin their reputation. But I didn’t. I took my rage to God as the psalmists and the prophets did before me.

I didn’t even ask God to take revenge on my enemies as the psalmists often did. I took my anger to God. I owned it. I was truthful to God about what I was struggling with, because I believe that the God who knows us intimately can handle anything we bring. I raged against the different types of White Christians who make the journey toward racial justice so hard.

But then, as the imprecatory psalms often do, I turned it. I prayed for God not to let anger and hatred overwhelm me. I asked to be able to continue to love those who hate me. I prayed to remain true to the biblical mandate for peace, justice and reconciliation even when I have very little hope of its possibility.

A few days ago, a Virginia pastor decided to post multiple screenshots of my prayer on Twitter, saying, “This kind of thinking is a direct result of CRT and is completely anti-biblical.” CRT is a reference to critical race theory, which conservatives have been attacking for months. Since then, his followers and other conservatives have targeted me for attack, harassing me through email, phone, and social media. In addition, they have bombarded my institution. Multiple conservative media outlets have picked up the story.

The “critics” – a word I use lightly since this is not good-faith engagement – are willfully misinterpreting the prayer (and also critical race theory), to an extent that can only be explained by hermeneutical incompetence or willful maliciousness. This is part of a pattern of abusive behavior that is being waged largely against Black women scholars and clergy who do intersectional justice work.

In all truth, my familial and personal experiences of racism have given me thousands, maybe even millions, of reasons to hate White people. It could easily be seen as justified. And I could find biblical precedent for it.

But dammit if God hasn’t given me a different spirit, one that insists on looking for goodness and possibility, one that holds holy rage and holy hope together. Many Black women can connect to that prayer, especially those of us who labor for justice within and beyond the church. Loving people who are committed to hating us – to disenfranchising us, incarcerating us, and abusing us in myriad other ways – is hard. And still, we persist.

The prayer is below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.